The Margin Note: How Fermat Was Inspired by Diophantus

22/07/2025

Almost every math enthusiast has heard Fermat’s phrase in some variation: “I have discovered a truly marvelous proof of this, which this margin is too narrow to contain.” Fewer, perhaps, have wondered: where exactly did Fermat write this note? What was the text he was reading when his hand paused at the margin?

The answer lies back in time, far from 17th century France, in the Alexandrian origins of algebra. Fermat wasn’t writing his notes on some random paper, but in the margin of an ancient Greek text: the “Arithmetica” by Diophantus of Alexandria.

Diophantus: The Pioneer of Algebraic Thinking

Before we delve into Fermat’s note, let’s get to know the “host” of the margin: Diophantus of Alexandria. Diophantus, who likely lived in the 3rd century CE, was a mathematician who drastically differed from his contemporaries. While the dominant mathematical tradition in ancient Greece was geometry (think Euclid and Pythagoras), Diophantus devoted himself to a different kind of problem: solving equations with numbers as unknowns.

His work, “Arithmetica,” consists of a series of problems and their solutions, and is considered one of the first systematic texts in the history of algebra. Diophantus used a primitive form of notation, not as developed as our modern algebra, but clearly beyond the purely rhetorical (verbal) description of problems of the time. He often sought rational solutions, that is, solutions that can be expressed as fractions of integers.

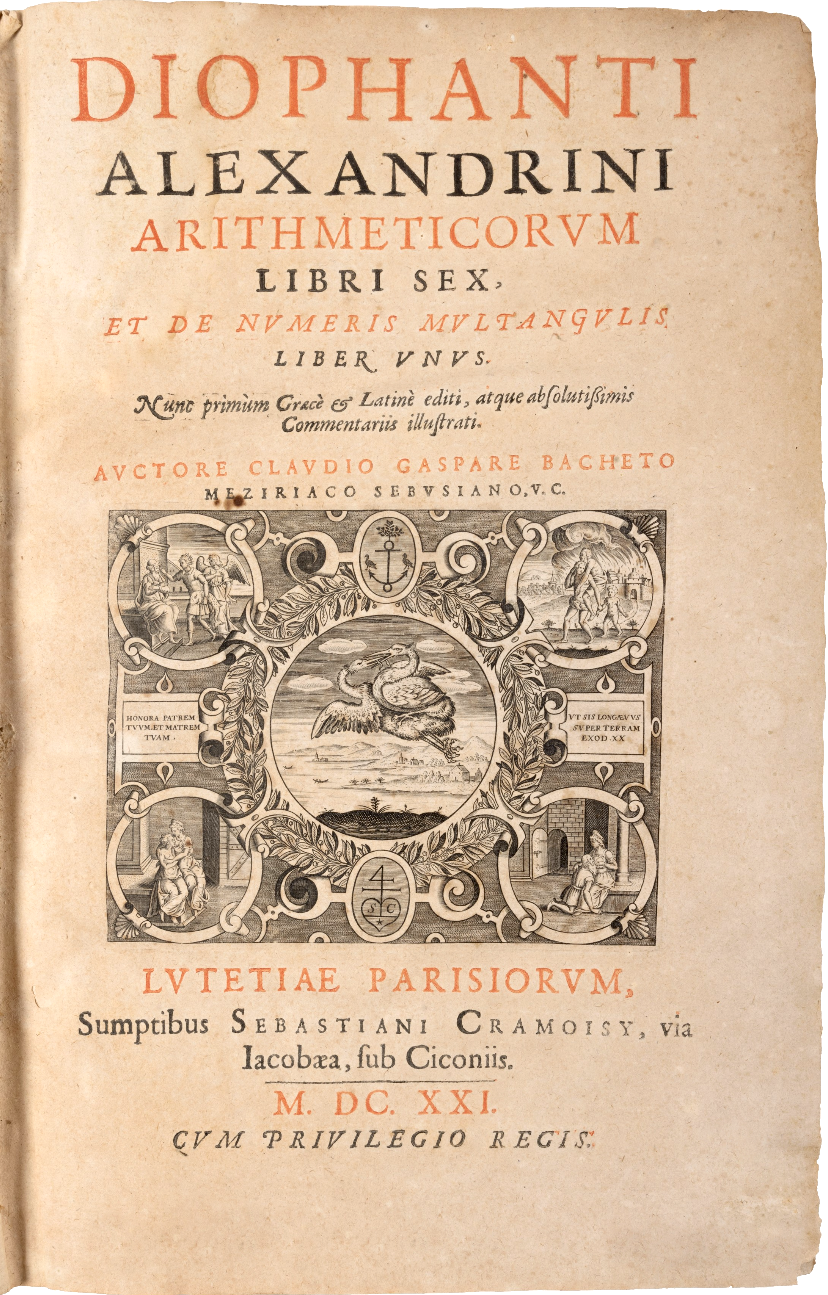

Cover of the 1670 edition of Diophantus’ “Arithmetica.” This work served as a source of inspiration for generations of mathematicians, including Fermat.

The Problem That Inspired Fermat:

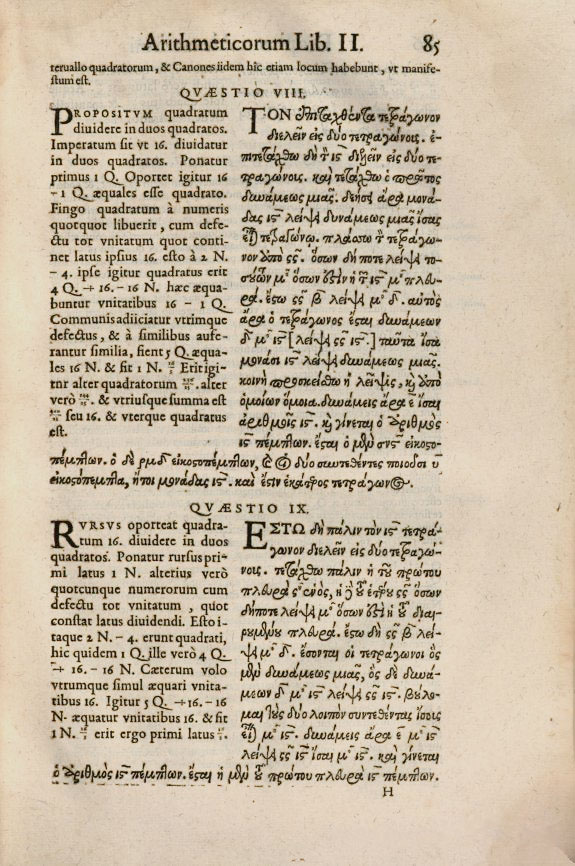

The exact point Fermat was reading was Problem 8 of Book II of “Arithmetica.” In the image below, we see the page from the 1670 edition that Fermat was studying.

The page with Problem 8 from Diophantus’ “Arithmetica”

Due to the quality and the font, it’s difficult to understand the Greek text. Using the capability offered by the StoicDocs platform to convert handwritten text to , we get the following result:

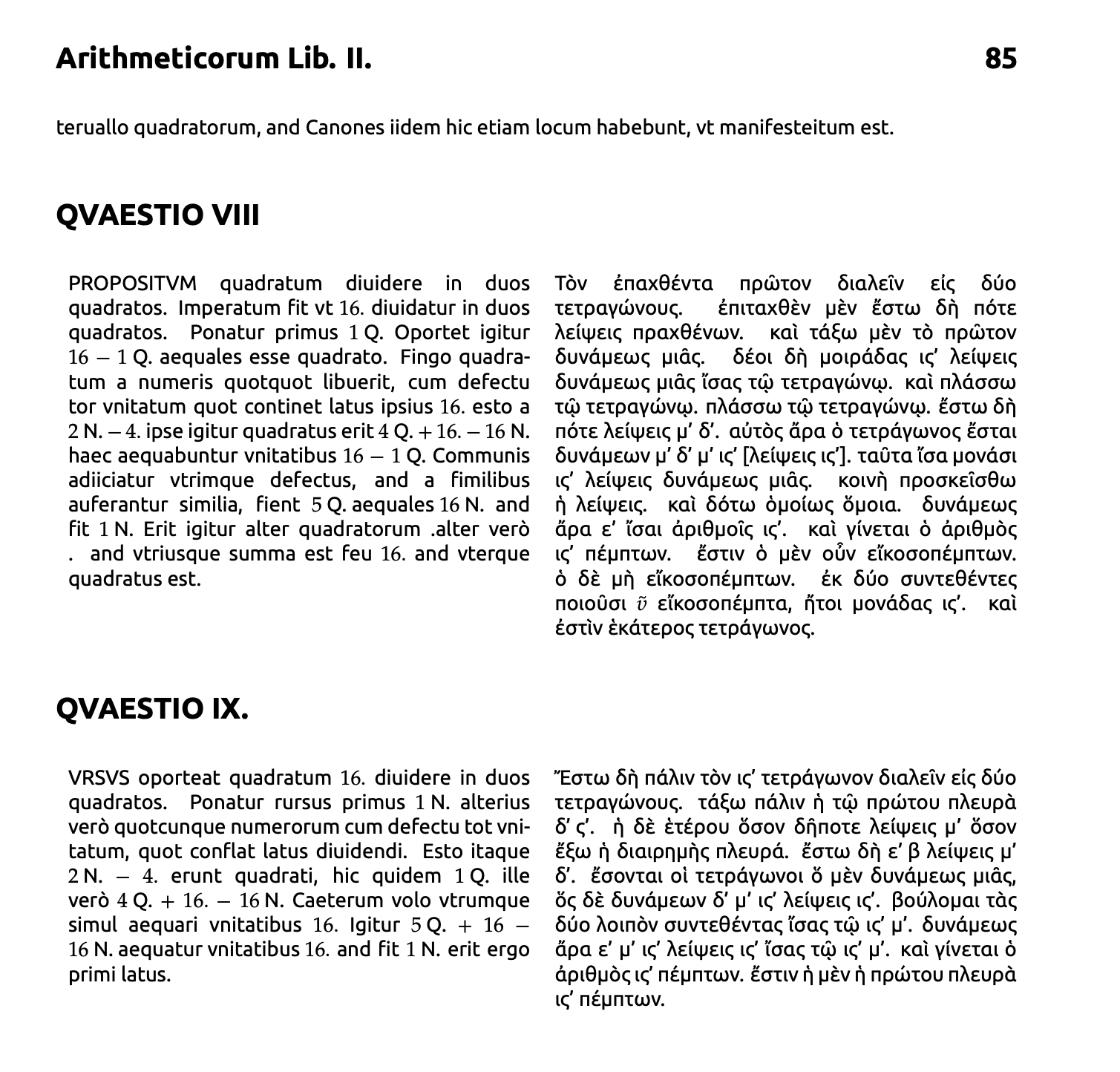

The page with Problem 8 from Diophantus’ “Arithmetica” in LaTeX

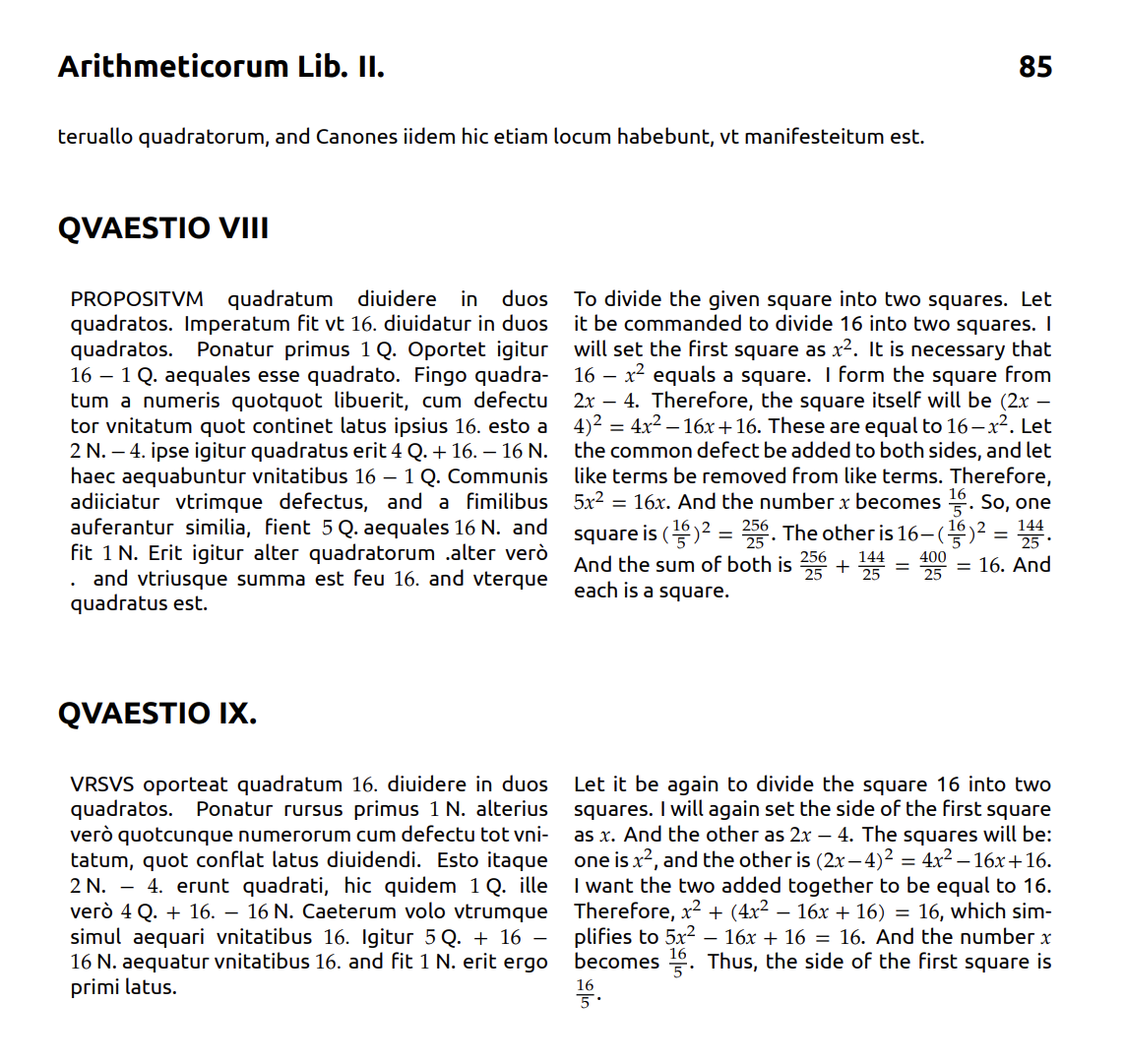

We asked StoicDocs to translate it in English and in terms of today’s algebra:

Translation of the problem in modern mathematical notation

Now we can fully understand this historic problem that inspired Fermat to make his famous conjecture:

The Problem: Splitting 16 into Two Squares

Diophantus poses the following problem: “We must divide a given square number into two other square numbers.” In this specific case, he asks us to divide the number 16 into two squares. In modern language, we’re looking for two numbers, let’s say x and y, such that

The core of Diophantus’ method is a very clever move: the choice of how he expresses the unknowns. This choice transforms a seemingly difficult problem into a simple, solvable equation.

Diophantus’ solution is a characteristic example of his method:

- He sets the first square as (where is an unknown number, the “side” of the square).

- This means that the second square must be .

- The key to Diophantine logic is the “clever” choice of the side of the second square. Instead of leaving as is, Diophantus sets the side of the second square as a linear expression related to the side of the original square () and the unknown . He chooses the side to be .

- Squaring this expression gives us: .

- Now, he equates this result with :

- With simple algebraic operations (adding and subtracting from both sides), the equation simplifies to: or

- From here, we find (the solution is rejected as trivial).

With , the two square numbers are:

- The first:

- The second:

And indeed: . The problem is solved with rational numbers.

Fermat’s Inspiration

Diophantus, with his “Arithmetica,” showed us how to find rational solutions for the equation . This problem, as we’ve seen, is elegantly solved. For Fermat, however, this solution wasn’t the end, but a starting point.

There, on this specific problem of splitting a square into two others, Fermat probably wondered: What would happen if we tried to do the same for cubes, or even fourth powers, or any other higher power? In his attempt to “break” such numbers (something that, as it turned out, is impossible for rational solutions), his hand paused at the margin of Diophantus’ book and wrote the words that would torment mathematicians for centuries:

“Cubum autem in duos cubos, aut quadratoquadratum in duos quadratoquadratos, et generaliter nullam in infinitum ultra quadratum potestatem in duos ejusdem nominis fas est dividere: cujus rei demonstrationem mirabilem sane detexi. Hanc marginis exiguitas non caperet.”

in modern English:

“It is impossible to separate a cube into two cubes, or a fourth power into two fourth powers, or in general, any power higher than the second, into two like powers. I have discovered a truly marvelous proof of this, which this margin is too narrow to contain.”

A Margin That Made History

Fermat’s brief note, written in the margin of an ancient work, reminds us how a seemingly small observation can trigger eternal mathematical pursuit. From Diophantus to the mathematicians of the 20th century, this challenge passed through generations, changing not only mathematics but also our very understanding of what “proof” means. Sometimes, the greatest stories begin in the most unlikely places.

The same technology that allowed us to analyze a text from the 3rd century in this article can do the same for your notes. If you have handwritten mathematical notes or any document you want to digitize and convert to LaTeX, try StoicDocs